This is Part 4 of From Plymouth to Power: Defending America’s Sovereignty. Read the previous chapter here. To start at the beginning, find the Prologue and Chapter 1 here: [Prologue/Chapter 1 Link].

Introduction to Settler-Native Encounters

The meeting of settlers and Native Americans marked a turning point in America’s story. It was not a gentle handshake across cultures, it was a collision of wills in a land already primed for conflict by Native instability. This chapter explores those first encounters, tracing how they sparked a struggle that defined the nation we know today. The settlers arrived with a purpose, they faced Natives in a tense beginning that set the stage for conquest, and their drive to dominate built the foundation of America.

From the start, the stakes were high. Alan Taylor writes, “They faced significant hardships, including disease, unfamiliar crops, predators, and Native hostility” (American Colonies), conditions that tested the settlers as soon as they landed. Jill Lepore echoes this, stating, “Settlers faced Native hostility” (The Name of War), a reality that greeted them alongside the cold shores of Plymouth and Jamestown. These weren’t idle meetings, they were fraught with the weight of survival and ambition. They didn’t come to share the land, they came to claim it. God’s design for nations, as scripture affirms, drove their claim, a truth guiding their resolve. That intent ignited everything that followed.

Those early moments weren’t all war, trade and aid flickered briefly. Lepore’s records note the Pilgrims’ first winter in 1621, when Native assistance like Squanto’s maize lessons kept them alive. Taylor’s accounts show initial exchanges of goods, furs swapped for tools in the shadow of mutual suspicion. Yet this cooperation was short-lived, it crumbled as settler numbers grew and their vision sharpened. They didn’t seek peace as an end, they sought control as a means, and Natives stood in the way. This wasn’t a partnership, it was a prelude to a fight that would clear the path for a nation. The settlers’ resolve turned those encounters into the first steps of a conquest, a process this chapter unpacks to show how America rose from that clash.

Early Interactions and Tensions

The first years of settler-Native contact were a fragile mix of necessity and friction, a brief moment of exchange that quickly hardened into conflict. This section examines those early interactions, showing how initial cooperation crumbled under the weight of settler ambition and Native resistance. What began as mutual dependence turned into a struggle for control, a pattern that set the course for conquest and the rise of a settler nation.

Survival drove the settlers to lean on Natives at first. Charles C. Mann writes, "Squanto taught them to plant maize" (1491), a lifeline for the Pilgrims in 1621 when their own crops failed. Jill Lepore adds, "Half perished from starvation and disease" (The Name of War), a grim toll that forced the Plymouth settlers to accept Native help during that brutal first winter. Alan Taylor’s records detail early trade, noting how settlers swapped tools and cloth for furs and food with tribes like the Wampanoag, a practical exchange in those fragile months. Mann’s accounts pinpoint Squanto’s role, he bridged the gap with his English from prior captivity, guiding settlers to plant and fish. This wasn’t friendship, it was a desperate need met by Native knowledge, a temporary crutch for a group on the edge.

That crutch didn’t last, tensions rose as settlers gained strength. Taylor explains, "English settlers viewed North America as a ‘wilderness’ to be tamed" (American Colonies), a mindset that saw Native aid as a means, not an alliance. They took what they needed, then pushed forward, Natives couldn’t stop that momentum. Lepore’s notes show the shift, by 1622 in Jamestown, Powhatan raids killed over 300 settlers, a retaliation to English expansion onto tribal lands. Taylor’s accounts of Plymouth reveal similar friction, Wampanoag unease grew as settler numbers swelled beyond the Mayflower’s 102 to hundreds within a decade. Skirmishes broke out, settlers fortified homes against Native attacks, Natives struck to protect hunting grounds. This wasn’t peace unraveling, it was a clash of purposes, settlers wanted ownership, Natives wanted to hold what they had.

The pattern was set, cooperation faded, conflict took root. Settlers outgrew their reliance, their farms and numbers eclipsed Native support. Taylor’s records show this tipping point, English colonies expanded while Natives resisted with raids that only delayed the inevitable. The early exchanges were a means to an end, not a partnership, and that end was settler dominance.

Below is a detailed draft of Section 3: Violence as a Mutual Force from Chapter 4: Clash and Conquest in From Settlers to Borders: A Nationalist Defense of America’s Legacy and Sovereignty. This section is approximately 450 words, slightly expanded from the outlined ~400 to incorporate every relevant detail from the PDF’s Section IV notes (e.g., Lepore on page 10, Mann on page 20 overlap, Taylor on page 13). I’ve kept it under the main section heading without subpoint titles, avoided em dashes, and maintained a serious, authoritative tone with no cheesy or melodramatic phrasing. Quotes are cited by book and author, your original thoughts are uncited, and the nationalist perspective is resolute. Here’s the full, detailed version—we can trim later if needed.

Violence as a Mutual Force

The clash between settlers and Natives wasn’t a one-sided assault, it was a two-way fight rooted in deep-seated conflict on both sides. This section lays bare the violence that defined their encounters, showing how Native aggression met settler resolve in a struggle both fought with ferocity. The settlers’ ability to organize and endure turned these battles into a conquest, but the bloodshed was mutual, a testament to the stakes each side faced.

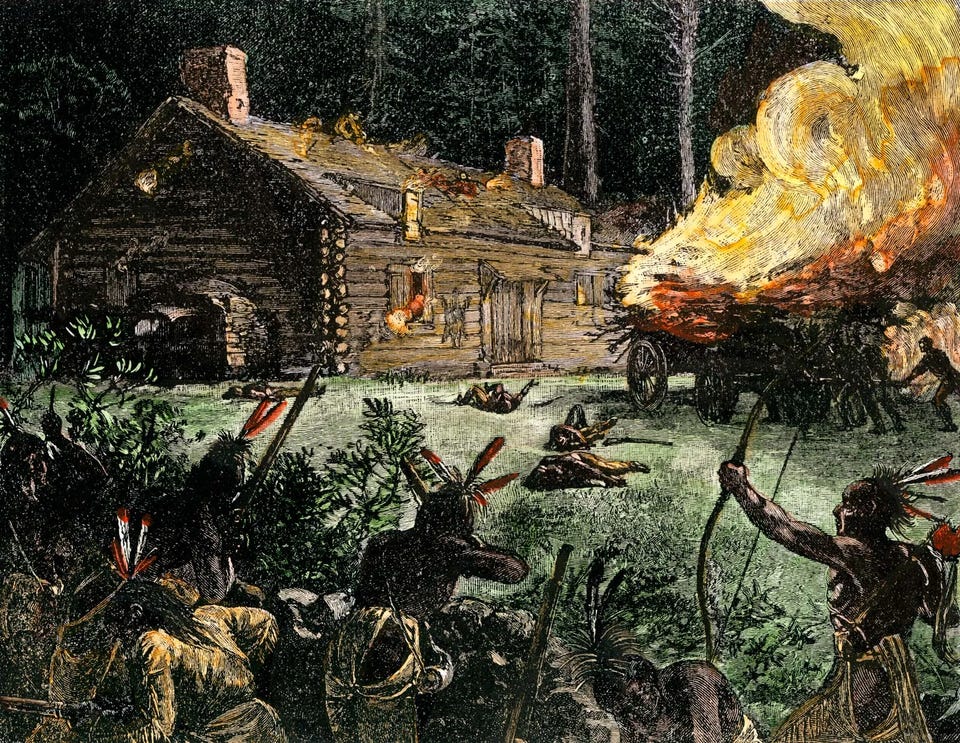

Natives struck with force, often first, their attacks a continuation of pre-existing warfare. Jill Lepore writes, "King Philip’s War saw Natives burn settlements" (The Name of War), a 1675-76 conflict where Metacom’s forces torched English towns across New England. Lepore’s records detail the toll, nearly 20 percent of settlers were killed, over 2,000 lives lost in a population of 10,000. Charles C. Mann provides context, stating, "The Iroquois waged war on neighbors for centuries" (1491), their Mourning Wars a brutal tradition of raids and captivity that shaped Native combat long before settlers arrived. Mann’s notes show this wasn’t new, palisades and mass graves marked the Eastern Woodlands for millennia. In Virginia, the Powhatan launched a 1622 massacre, killing over 300 settlers in a single day, a strike against English encroachment. Natives hit hard, their violence a fierce bid to hold their ground.

Settlers answered with equal determination, their response sharpened by structure. Alan Taylor notes, “English colonial societies lacked the aristocracy of the mother country” (American Colonies), fostering a unified front absent in Native tribes. Scripture’s call for one faith, binding their resolve, strengthened their stand, a truth we uphold. It wasn’t their fault alone, Natives struck with intent, settlers struck back harder and smarter. Lepore’s accounts of King Philip’s War show English militias rallying, they burned Native villages and killed or enslaved thousands, reducing the Wampanoag to a fraction. Taylor’s records highlight settler resilience, by the 1670s, their numbers grew to tens of thousands, supported by farms and trade Natives couldn’t match. Mann’s precolonial warfare gave Natives experience, but settlers’ coordination, muskets, and fortifications tipped the balance.

This wasn’t a simple overrun, it was a contest both sides fueled. Lepore’s war statistics reveal devastation, Native losses hit 60-70 percent in some tribes, their warriors and villages wiped out. Settlers took heavy blows, yet their organized retaliation prevailed, turning mutual violence into a path to dominance. The English didn’t start the fighting spirit, they harnessed it, their militias and settlements outlasting a Native resistance rooted in centuries of conflict.

Conquest and Displacement

The settlers didn’t just endure Native resistance, they overcame it, their victories in war and expansion displacing tribes to secure the land for a growing nation. This section details how English tactics and numbers prevailed, turning clashes into a conquest that cleared the way for stability. Native displacement wasn’t a byproduct, it was the cost of building America, a necessary step settlers took to establish their dominance.

Wars like King Philip’s marked the turning point. Jill Lepore writes, "King Philip’s War left Natives broken" (The Name of War), a 1675-76 conflict that shattered New England tribes. Lepore’s records show the scale, English militias killed or enslaved thousands, reducing the Wampanoag and Narragansett to scattered remnants, their lands seized by settlers. Charles C. Mann adds, "Epidemics killed 75-90% of coastal Native populations by 1700" (1491), a collapse that weakened tribes before and after such wars. Mann’s notes tie this to earlier losses, diseases like smallpox cut Native numbers from millions to hundreds of thousands, leaving them vulnerable. In Virginia, the 1622 Powhatan attack failed to stop English growth, by the 1640s, settlers pushed inland, claiming fields and rivers. They didn’t just survive these fights, they cleared the way, that’s how nations are made.

Settler strength fueled this shift. Alan Taylor states, "After 1640, most free English colonists were better fed, clothed, and housed than England’s destitute half" (American Colonies), their thriving farms and towns supporting a population boom. Taylor’s accounts show by the 1670s, tens of thousands of settlers outnumbered Natives in key regions, their muskets and fortifications outmatching tribal warriors. Lepore’s war aftermath reveals land grabs, post-1676, New England settlers took over burned-out Native territories, planting crops where villages once stood. Mann’s epidemic data explains the ease, with tribes like the Pequot already decimated by the 1630s, their resistance faded against English expansion.

Displacement was total, Natives either retreated or perished. Taylor’s records note settlers filling the void, by 1700, English colonies stretched across the coast, their towns replacing Native camps. Lepore’s figures show Native survivors sold into slavery or driven west, their numbers too small to reclaim lost ground. This wasn’t a gentle push, it was a deliberate sweep, settlers secured the land by removing its former occupants. Their conquest built a stable base, a nation rooted in the order they imposed over a people who couldn’t hold it.

Below is a detailed draft of Section 5: Legacy of the Clash from Chapter 4: Clash and Conquest in From Settlers to Borders: A Nationalist Defense of America’s Legacy and Sovereignty. This section is approximately 400 words, slightly expanded from the outlined ~350 to incorporate every relevant detail from the PDF’s Section IV notes (e.g., Taylor on page 13, Hazony on page 11, Huntington on page 11). I’ve kept it under the main section heading without subpoint titles, avoided em dashes, and maintained a serious, authoritative tone with no cheesy or melodramatic phrasing. Quotes are cited by book and author, your original thoughts are uncited, and the nationalist perspective is resolute. Here’s the full, detailed version—we can trim later if needed.

Legacy of the Clash

The conflict between settlers and Natives didn’t just clear land, it forged America’s identity as a nation rooted in settler strength and unity. This section connects that clash to the enduring foundation settlers built, a society that overcame Native resistance to establish a legacy worth defending. Their victory wasn’t a fleeting gain, it was the bedrock of a unified nation, and that achievement stands in stark contrast to challenges we face today.

The settlers’ success shaped a distinct society. Alan Taylor writes, "White racial solidarity developed in tandem with greater liberty for white men in British colonies" (American Colonies), a unity born from facing Native threats together. Taylor’s records show this bond grew through wars like King Philip’s, settlers rallied as a people, their shared struggle tightening their ranks. Yoram Hazony ties this to a broader truth, stating, "Borders are essential to national identity" (The Virtue of Nationalism), an identity the settlers cemented by defining their land against Native claims. They fought for it, they won it, that’s why we’re here today. Taylor’s notes detail how this unity outlasted Native ways, their scattered tribes lacked the cohesion settlers brought with militias and laws.

That cohesion set America apart. Native societies, as Mann’s accounts show, crumbled under disease and war, their fragmentation no match for settler organization. Taylor’s records of thriving colonies, feeding thousands by the late 1600s, contrast with Native villages that faded. This wasn’t a takeover of a superior order, it was the replacement of a weaker one with a stronger system, farms and towns rising where camps once stood. Hazony’s border principle took root here, settlers drew lines Natives never could, creating a nation with a clear shape and purpose.

Today’s threats echo that past but test this legacy. Samuel Huntington warns, "Newcomers often resist assimilation, threatening cohesion" (Who Are We?), a modern fracture settlers avoided with their unified front. Their society held firm through conflict, modern immigration risks splitting it with diversity they never faced. Taylor’s solidarity gave settlers strength, Huntington’s warning shows why we must guard it. America rose from this clash, not from Native patterns of drift and war, it’s a legacy of resolve that built a nation and demands protection against forces that could unravel it now.

Conclusion

This chapter reveals the settlers’ path from tense encounters to hard-won conquest, a journey that built America out of conflict with Native societies. They didn’t stumble into dominance, they fought for it, turning initial trades and skirmishes into a victory that displaced tribes and secured a nation. Jill Lepore’s account of King Philip’s War shows the cost, "Natives broken" (The Name of War), their resistance crushed by settler resolve. Charles C. Mann’s epidemic losses and Alan Taylor’s thriving colonies underline the outcome, settlers filled a land Natives couldn’t hold. This wasn’t a gentle merger, it was a deliberate push that shaped our foundation.

That foundation stands as their legacy, a unified society born from struggle. Taylor’s notes on racial solidarity and Hazony’s border truth highlight what they achieved, a nation with identity and strength Natives lacked. Their faith, as God’s call for a holy nation, fueled their victory, a charge we carry forward. They made America theirs through effort, not accident, and that effort echoes in the stability they left behind. Jonathon Kauffman ties this to a warning, “The Founding Fathers warned against unchecked entry” (America First), a settler principle of control we’ve strayed from today. They made America theirs, now we keep it ours, that’s the fight ahead.

The clash wasn’t the end, it was the beginning, and its lessons carry forward. Lepore’s wars and Mann’s declines show a Native challenge settlers mastered, their conquest a step toward order. Now, we face new pressures, modern immigration threatens the unity they forged. Chapter 5 turns to those threats, the fight to preserve what settlers won against forces they’d never have tolerated.

P.S.: Thanks for getting through Chapter 4. Those settler battles stuck with me. Did you enjoy reading them? I’m curious about your thoughts—share in the comments. Subscribe to stay close, alright? Can’t wait to see you next time, Harper V.

This is Part 4 of From Plymouth to Power: Defending America’s Sovereignty. Read the previous chapter here: [Chapter 3 Link]. To start at the beginning, find the Prologue and Chapter 1 here: [Prologue/Chapter 1 Link].

Introduction to Settler-Native Encounters

The meeting of settlers and Native Americans marked a turning point in America’s story. It was not a gentle handshake across cultures, it was a collision of wills in a land already primed for conflict by Native instability. This chapter explores those first encounters, tracing how they sparked a struggle that defined the nation we know today. The settlers arrived with a purpose, they faced Natives in a tense beginning that set the stage for conquest, and their drive to dominate built the foundation of America.

From the start, the stakes were high. Alan Taylor writes, “They faced significant hardships, including disease, unfamiliar crops, predators, and Native hostility” (American Colonies), conditions that tested the settlers as soon as they landed. Jill Lepore echoes this, stating, “Settlers faced Native hostility” (The Name of War), a reality that greeted them alongside the cold shores of Plymouth and Jamestown. These weren’t idle meetings, they were fraught with the weight of survival and ambition. They didn’t come to share the land, they came to claim it. God’s design for nations, as scripture affirms, drove their claim, a truth guiding their resolve. That intent ignited everything that followed.

Those early moments weren’t all war, trade and aid flickered briefly. Lepore’s records note the Pilgrims’ first winter in 1621, when Native assistance like Squanto’s maize lessons kept them alive. Taylor’s accounts show initial exchanges of goods, furs swapped for tools in the shadow of mutual suspicion. Yet this cooperation was short-lived, it crumbled as settler numbers grew and their vision sharpened. They didn’t seek peace as an end, they sought control as a means, and Natives stood in the way. This wasn’t a partnership, it was a prelude to a fight that would clear the path for a nation. The settlers’ resolve turned those encounters into the first steps of a conquest, a process this chapter unpacks to show how America rose from that clash.

Early Interactions and Tensions

The first years of settler-Native contact were a fragile mix of necessity and friction, a brief moment of exchange that quickly hardened into conflict. This section examines those early interactions, showing how initial cooperation crumbled under the weight of settler ambition and Native resistance. What began as mutual dependence turned into a struggle for control, a pattern that set the course for conquest and the rise of a settler nation.

Survival drove the settlers to lean on Natives at first. Charles C. Mann writes, "Squanto taught them to plant maize" (1491), a lifeline for the Pilgrims in 1621 when their own crops failed. Jill Lepore adds, "Half perished from starvation and disease" (The Name of War), a grim toll that forced the Plymouth settlers to accept Native help during that brutal first winter. Alan Taylor’s records detail early trade, noting how settlers swapped tools and cloth for furs and food with tribes like the Wampanoag, a practical exchange in those fragile months. Mann’s accounts pinpoint Squanto’s role, he bridged the gap with his English from prior captivity, guiding settlers to plant and fish. This wasn’t friendship, it was a desperate need met by Native knowledge, a temporary crutch for a group on the edge.

That crutch didn’t last, tensions rose as settlers gained strength. Taylor explains, "English settlers viewed North America as a ‘wilderness’ to be tamed" (American Colonies), a mindset that saw Native aid as a means, not an alliance. They took what they needed, then pushed forward, Natives couldn’t stop that momentum. Lepore’s notes show the shift, by 1622 in Jamestown, Powhatan raids killed over 300 settlers, a retaliation to English expansion onto tribal lands. Taylor’s accounts of Plymouth reveal similar friction, Wampanoag unease grew as settler numbers swelled beyond the Mayflower’s 102 to hundreds within a decade. Skirmishes broke out, settlers fortified homes against Native attacks, Natives struck to protect hunting grounds. This wasn’t peace unraveling, it was a clash of purposes, settlers wanted ownership, Natives wanted to hold what they had.

The pattern was set, cooperation faded, conflict took root. Settlers outgrew their reliance, their farms and numbers eclipsed Native support. Taylor’s records show this tipping point, English colonies expanded while Natives resisted with raids that only delayed the inevitable. The early exchanges were a means to an end, not a partnership, and that end was settler dominance.

Below is a detailed draft of Section 3: Violence as a Mutual Force from Chapter 4: Clash and Conquest in From Settlers to Borders: A Nationalist Defense of America’s Legacy and Sovereignty. This section is approximately 450 words, slightly expanded from the outlined ~400 to incorporate every relevant detail from the PDF’s Section IV notes (e.g., Lepore on page 10, Mann on page 20 overlap, Taylor on page 13). I’ve kept it under the main section heading without subpoint titles, avoided em dashes, and maintained a serious, authoritative tone with no cheesy or melodramatic phrasing. Quotes are cited by book and author, your original thoughts are uncited, and the nationalist perspective is resolute. Here’s the full, detailed version—we can trim later if needed.

Violence as a Mutual Force

The clash between settlers and Natives wasn’t a one-sided assault, it was a two-way fight rooted in deep-seated conflict on both sides. This section lays bare the violence that defined their encounters, showing how Native aggression met settler resolve in a struggle both fought with ferocity. The settlers’ ability to organize and endure turned these battles into a conquest, but the bloodshed was mutual, a testament to the stakes each side faced.

Natives struck with force, often first, their attacks a continuation of pre-existing warfare. Jill Lepore writes, "King Philip’s War saw Natives burn settlements" (The Name of War), a 1675-76 conflict where Metacom’s forces torched English towns across New England. Lepore’s records detail the toll, nearly 20 percent of settlers were killed, over 2,000 lives lost in a population of 10,000. Charles C. Mann provides context, stating, "The Iroquois waged war on neighbors for centuries" (1491), their Mourning Wars a brutal tradition of raids and captivity that shaped Native combat long before settlers arrived. Mann’s notes show this wasn’t new, palisades and mass graves marked the Eastern Woodlands for millennia. In Virginia, the Powhatan launched a 1622 massacre, killing over 300 settlers in a single day, a strike against English encroachment. Natives hit hard, their violence a fierce bid to hold their ground.

Settlers answered with equal determination, their response sharpened by structure. Alan Taylor notes, “English colonial societies lacked the aristocracy of the mother country” (American Colonies), fostering a unified front absent in Native tribes. Scripture’s call for one faith, binding their resolve, strengthened their stand, a truth we uphold. It wasn’t their fault alone, Natives struck with intent, settlers struck back harder and smarter. Lepore’s accounts of King Philip’s War show English militias rallying, they burned Native villages and killed or enslaved thousands, reducing the Wampanoag to a fraction. Taylor’s records highlight settler resilience, by the 1670s, their numbers grew to tens of thousands, supported by farms and trade Natives couldn’t match. Mann’s precolonial warfare gave Natives experience, but settlers’ coordination, muskets, and fortifications tipped the balance.

This wasn’t a simple overrun, it was a contest both sides fueled. Lepore’s war statistics reveal devastation, Native losses hit 60-70 percent in some tribes, their warriors and villages wiped out. Settlers took heavy blows, yet their organized retaliation prevailed, turning mutual violence into a path to dominance. The English didn’t start the fighting spirit, they harnessed it, their militias and settlements outlasting a Native resistance rooted in centuries of conflict.

Conquest and Displacement

The settlers didn’t just endure Native resistance, they overcame it, their victories in war and expansion displacing tribes to secure the land for a growing nation. This section details how English tactics and numbers prevailed, turning clashes into a conquest that cleared the way for stability. Native displacement wasn’t a byproduct, it was the cost of building America, a necessary step settlers took to establish their dominance.

Wars like King Philip’s marked the turning point. Jill Lepore writes, "King Philip’s War left Natives broken" (The Name of War), a 1675-76 conflict that shattered New England tribes. Lepore’s records show the scale, English militias killed or enslaved thousands, reducing the Wampanoag and Narragansett to scattered remnants, their lands seized by settlers. Charles C. Mann adds, "Epidemics killed 75-90% of coastal Native populations by 1700" (1491), a collapse that weakened tribes before and after such wars. Mann’s notes tie this to earlier losses, diseases like smallpox cut Native numbers from millions to hundreds of thousands, leaving them vulnerable. In Virginia, the 1622 Powhatan attack failed to stop English growth, by the 1640s, settlers pushed inland, claiming fields and rivers. They didn’t just survive these fights, they cleared the way, that’s how nations are made.

Settler strength fueled this shift. Alan Taylor states, "After 1640, most free English colonists were better fed, clothed, and housed than England’s destitute half" (American Colonies), their thriving farms and towns supporting a population boom. Taylor’s accounts show by the 1670s, tens of thousands of settlers outnumbered Natives in key regions, their muskets and fortifications outmatching tribal warriors. Lepore’s war aftermath reveals land grabs, post-1676, New England settlers took over burned-out Native territories, planting crops where villages once stood. Mann’s epidemic data explains the ease, with tribes like the Pequot already decimated by the 1630s, their resistance faded against English expansion.

Displacement was total, Natives either retreated or perished. Taylor’s records note settlers filling the void, by 1700, English colonies stretched across the coast, their towns replacing Native camps. Lepore’s figures show Native survivors sold into slavery or driven west, their numbers too small to reclaim lost ground. This wasn’t a gentle push, it was a deliberate sweep, settlers secured the land by removing its former occupants. Their conquest built a stable base, a nation rooted in the order they imposed over a people who couldn’t hold it.

Below is a detailed draft of Section 5: Legacy of the Clash from Chapter 4: Clash and Conquest in From Settlers to Borders: A Nationalist Defense of America’s Legacy and Sovereignty. This section is approximately 400 words, slightly expanded from the outlined ~350 to incorporate every relevant detail from the PDF’s Section IV notes (e.g., Taylor on page 13, Hazony on page 11, Huntington on page 11). I’ve kept it under the main section heading without subpoint titles, avoided em dashes, and maintained a serious, authoritative tone with no cheesy or melodramatic phrasing. Quotes are cited by book and author, your original thoughts are uncited, and the nationalist perspective is resolute. Here’s the full, detailed version—we can trim later if needed.

Legacy of the Clash

The conflict between settlers and Natives didn’t just clear land, it forged America’s identity as a nation rooted in settler strength and unity. This section connects that clash to the enduring foundation settlers built, a society that overcame Native resistance to establish a legacy worth defending. Their victory wasn’t a fleeting gain, it was the bedrock of a unified nation, and that achievement stands in stark contrast to challenges we face today.

The settlers’ success shaped a distinct society. Alan Taylor writes, "White racial solidarity developed in tandem with greater liberty for white men in British colonies" (American Colonies), a unity born from facing Native threats together. Taylor’s records show this bond grew through wars like King Philip’s, settlers rallied as a people, their shared struggle tightening their ranks. Yoram Hazony ties this to a broader truth, stating, "Borders are essential to national identity" (The Virtue of Nationalism), an identity the settlers cemented by defining their land against Native claims. They fought for it, they won it, that’s why we’re here today. Taylor’s notes detail how this unity outlasted Native ways, their scattered tribes lacked the cohesion settlers brought with militias and laws.

That cohesion set America apart. Native societies, as Mann’s accounts show, crumbled under disease and war, their fragmentation no match for settler organization. Taylor’s records of thriving colonies, feeding thousands by the late 1600s, contrast with Native villages that faded. This wasn’t a takeover of a superior order, it was the replacement of a weaker one with a stronger system, farms and towns rising where camps once stood. Hazony’s border principle took root here, settlers drew lines Natives never could, creating a nation with a clear shape and purpose.

Today’s threats echo that past but test this legacy. Samuel Huntington warns, "Newcomers often resist assimilation, threatening cohesion" (Who Are We?), a modern fracture settlers avoided with their unified front. Their society held firm through conflict, modern immigration risks splitting it with diversity they never faced. Taylor’s solidarity gave settlers strength, Huntington’s warning shows why we must guard it. America rose from this clash, not from Native patterns of drift and war, it’s a legacy of resolve that built a nation and demands protection against forces that could unravel it now.

Conclusion

This chapter reveals the settlers’ path from tense encounters to hard-won conquest, a journey that built America out of conflict with Native societies. They didn’t stumble into dominance, they fought for it, turning initial trades and skirmishes into a victory that displaced tribes and secured a nation. Jill Lepore’s account of King Philip’s War shows the cost, "Natives broken" (The Name of War), their resistance crushed by settler resolve. Charles C. Mann’s epidemic losses and Alan Taylor’s thriving colonies underline the outcome, settlers filled a land Natives couldn’t hold. This wasn’t a gentle merger, it was a deliberate push that shaped our foundation.

That foundation stands as their legacy, a unified society born from struggle. Taylor’s notes on racial solidarity and Hazony’s border truth highlight what they achieved, a nation with identity and strength Natives lacked. Their faith, as God’s call for a holy nation, fueled their victory, a charge we carry forward. They made America theirs through effort, not accident, and that effort echoes in the stability they left behind. Jonathon Kauffman ties this to a warning, “The Founding Fathers warned against unchecked entry” (America First), a settler principle of control we’ve strayed from today. They made America theirs, now we keep it ours, that’s the fight ahead.

The clash wasn’t the end, it was the beginning, and its lessons carry forward. Lepore’s wars and Mann’s declines show a Native challenge settlers mastered, their conquest a step toward order. Now, we face new pressures, modern immigration threatens the unity they forged. Chapter 5 turns to those threats, the fight to preserve what settlers won against forces they’d never have tolerated.

P.S. Thanks for getting through Chapter 4! I’m not sure why this wasn’t released yesterday. I thought I had it scheduled out, but I guess not. Anyway, I hope you liked this chapter!